Review By: Romasa Jami

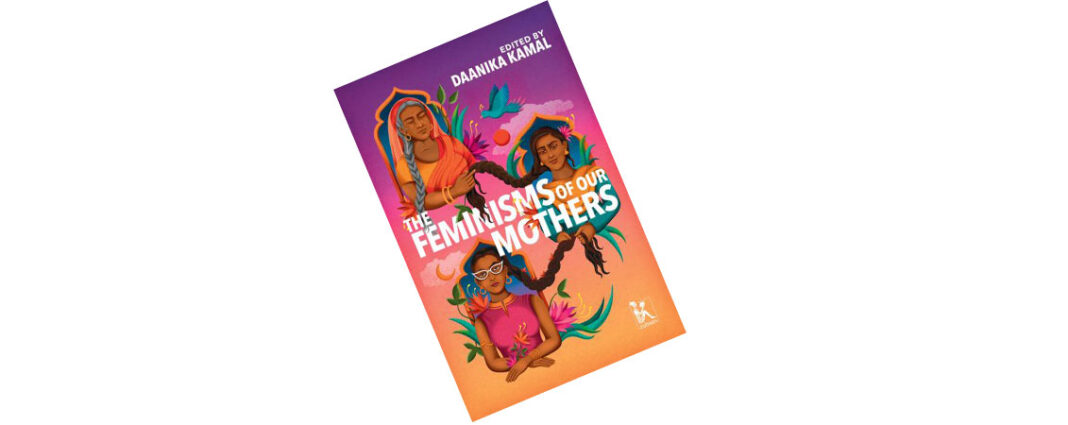

I was captivated by the distinct illustration by Samya Arif on the cover, showcasing women of 3 generations braiding each other’s hair. It was striking and deeply reflected the lesson of resistance and endurance our mothers passed to us. The Feminism of Our Mothers is a collection of essays from prominent women’s rights advocates from across Pakistan working in diverse fields. Edited by Danika Kamal who is a published author and editor, specializes in human rights law with a focus on ensuring access to justice and safeguarding the rights of marginalized sections of society.

Exploring each essay fills you with a plethora of emotions and relatability to an unimaginable extent as though it is me writing about my experiences and learnings from my mother. The commonality that we all share is perhaps the gender we embody and the active marginalization at the hands of impractical patriarchal structures which have very little to no space for women of choice.

The essays remarkably weave the journey of our feminist ancestors marching the streets in 1983 to their daughters dancing and chanting on streets at the Aurat march since 2018, vividly illuminating the defiance against the nuanced, delicate threads of patriarchy that oppress women.

As Aiman Rizvi writes, “Found in the crevices of every day that those small acts of resistance and negotiation were just as political as demanding legislative reforms.” The essays reflect how resistance to the patriarchy has persisted ever since women their bodies, and individuality were colonized by patriarchal values structures.

The book swiftly walks us through the variety of interpretations and reactions to the established values, revealing how confronting patriarchy prompted our mothers to redefine these norms or at least challenge them in their limited capacities. Suraiya Anjum sums it up in a sentence as she writes, “He believed he knew her place, and she refused to see it?

Daanika Kamaal shares in her essay how we conveniently perceive that the daughter of a divorced woman is bound to get divorced too, as though coming from a broken home guarantees that if that woman tries to build a home is meant to be inherently fractured. She redefines it as the daughter of an emancipated woman is bound to emancipate herself too. Reflecting on the resilience of the contemporary women, they refuse to diminish their worth or allow the failed structures to undermine their value which serves as a testament to the fundamental essence of choice in human existence.

Considering this let’s delve into a part of Maria Amir’s essay, she writes, “It is interesting that synonyms of the word “settled” generally include “resolved” or “finished”, as if young women are incomplete, enrolment forms that need to be filled out and signed off on-time lest they expired and exceeded their usefulness.” Expanding on this Ayesha Azher sheds light on the societal narrative that conditions us to view marriage and raising a family as the pinnacle of women’s fulfilment. Little do we realize if it is a conscious choice or a coerced choice, for most we stay oblivious to how we “Actually” feel towards this idea. It is a stark reality how these internalized values have made a home somewhere in the subliminal darkness of our minds and hearts. To conform and be embraced, we navigate through the tunnel of patriarchy towards societal acceptance.

Speaking of internalizing, Zoya Rehman writes, “as women, we are a firm grip of our mothers before we are in the grip of patriarchy.” As she explores the intricacy of her relationship with her mother whom she refers to as her nurturer and her tormentor, her essay allows us to understand the internalized patriarchy. This perpetuates a cycle where mothers oftentimes impose their silence onto their daughters and envy them for their non-conformity. They are fed that the only contentment of a woman lies in compliance. Until they witness the grim reality of life as beautifully penned down by Suleha Kamal, “Childhood, in some way is an equalizer. Children- boys and girls are all relegated to the margins of society, so it comes as a shock in adolescence that society only means for half of us to stay there forever.”

Subsequently, Zoya expresses her yearning to carry hope to the feminist spaces and not dreams broken by patriarchy. The book frequently mentions how the feminist movements in Pakistan have to mitigate themselves through cultural sensitivities and aversion of women associating themselves with this “F” word. This paradox persists despite the substantial contributions of indigenous women in shaping us and their significant role in leading us to an inclusive societal framework. The essence of this can also be witnessed in the feminist struggles of Pakistani women which Maheen Humayun eloquently expresses as, “Feminist labour can also come in shapes of supporting the people around them, being homemakers, acknowledging the past, or even simply being open and willing to have a conversation. This is feminist labour too, and none of it should be discounted.

The book further highlights the significance of intersectionality of our women’s rights advocacy acknowledging the contrasting privileges afforded to cis-gendered women while shedding light on the marginalized status of gender-diverse individuals. It illustrates patriarchy as a failed system that, beyond oppressing women and gender-diverse people, has also extended its impact to affect men, sparing none from its wrath. These essays offer a poignant glimpse into the multifaceted reality of the struggles for women’s liberation which is not fixated but a process, a tapestry woven with learning, good and bad decisions to build an inclusive community to which we all belong. As Aiman Rizvi writes, “To the new shelter seekers, you can do it again, teach us how to do it better.”

It is disheartening to mention that one of the essays, “What is Behind You” by Sadia Khatri which talks about the struggle of a Pakistani woman navigating faith, friendship and hurdles in motherhood choices, was excluded from the Pakistani edition of the book published by liberty books. Censorship like such often neglects to honour feminist voices, there lies an eager need to control narratives reflecting a larger societal trend towards restricting constructive social and cultural discourses and questioning our collective direction as critical thinkers. “What is behind you”, didn’t challenge any values but instead exposed critical social issue which demands discourse and attention.

These essays serve as a portal for the reader into the complexities, intimacies and struggles of the author through which they find solidarity, after all, feminism has taught us to find equity in difference and has sowed the seeds of a desire to put down the burden of patriarchy from our shoulders and liberate us all; our mothers, our daughters and ourselves.

The writer is a lawyer and human rights advocate. She can be reached at [email protected]